COWORKING BEFORE COWORKING #1: Warhol’s Factory

Before the term “coworking” existed, there were already places where creativity, community, and commerce collided. They were not called incubators or creative hubs, but they performed the same function. These were spaces where artists, thinkers, and entrepreneurs gathered to experiment and work outside conventional systems.

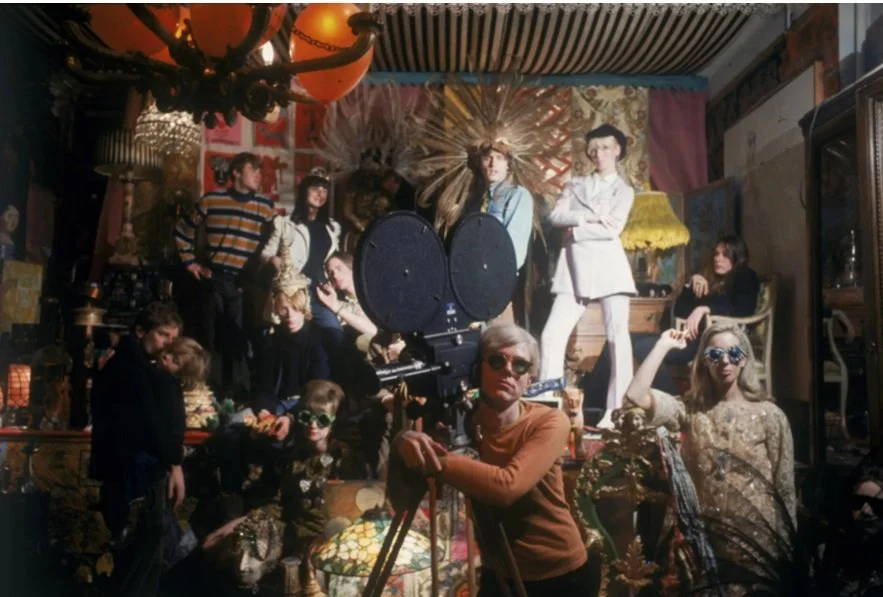

One of the most famous of these was Andy Warhol’s Factory, perhaps the most iconic shared creative space of the twentieth century.

The Silver Factory, 231 East 47th Street, Manhattan

Warhol opened his first Factory in 1964 at 231 East 47th Street in Midtown Manhattan. The space was decorated entirely in silver. The walls, ceiling, and furniture were wrapped in foil and coated in metallic paint by artist Billy Name. This aesthetic decision was both minimalist and excessive. It reflected the industrial age’s fascination with machinery and surface while creating a dreamlike environment that blurred the boundaries between art, commerce, and performance (Bockris, 2003).

The Factory was simultaneously a studio, film set, gallery, and party venue. Warhol shot many of his underground films there, including Vinyl (1965) and Chelsea Girls (1966). The Velvet Underground rehearsed within the same walls, merging avant-garde art with experimental music. Screenprints of Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor were made on site, often by untrained visitors or friends. Mistakes became part of the aesthetic.

Gallerists were sold unframed canvases often made by attendees of the various happenings at The Factory, which were nevertheless sold as unique Warhols. This approach to artistic production was detached yet democratic, parodying the production lines of industrial capitalism and redefining the idea of artistic authorship. The Factory was a site of production but also a social experiment in distributed creativity.

A Factory that Manufactured Culture

Warhol’s choice of the word Factory was deliberate. In an era defined by Fordist mass production, he turned the language of industry inward. His Factory did not produce cars or machinery. It produced images, myths, and cultural moments. In place of hierarchy, it cultivated participation. It embodied what Walter Benjamin described as the paradox of mechanical reproduction, where art and labour, originality and repetition, become inseparable (Benjamin, 1936).

What emerged was a new model of creative work: collaborative, performative, and open to influence. Warhol’s practice blurred the line between fine art and popular culture, while the Factory blurred the distinction between artist and assistant, professional and amateur, work and play.

The First Coworking Space?

If coworking today represents a shift from private offices to shared environments that value flexibility, collaboration, and community, then Warhol’s Factory anticipated this model by more than half a century. It was a precursor to the creative economy, where value is generated through networks rather than hierarchies, and where work and identity merge.

The Factory’s participants were artists, musicians, writers, photographers, and drifters. these all coexisted in an open system of creative exchange. Like a contemporary coworking space, it functioned as both a site of production and a stage for self-presentation. The Factory demonstrated that creative energy thrives not in isolation but through proximity, friction, and experimentation.

The Rebel Connection

At Rebel Workspace, we take inspiration from the Factory as an organisational and ideological model, as well as just a beacon of smouldering cool which we want to emulate. The Factory teaches us that true coworking is not about ergonomic chairs or filtered water. It is about creating environments where risk, experimentation, and collaboration are encouraged. The Factory reminds us that innovation rarely comes from corporate settings. It happens in the margins, in spaces where people are free to make, to fail, and to invent together.

Warhol’s Factory was more than a studio. It was an early prototype for the coworking ethos, a collective reimagining of what work could be.

References

Benjamin, W. (1936) The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. New York: Schocken Books.

Bockris, V. (2003) Warhol: The Biography. London: Da Capo Press.

Colacello, B. (1990) Holy Terror: Andy Warhol Close Up. New York: HarperCollins.

Watson, S. (2003) Factory Made: Warhol and the Sixties. New York: Pantheon Books.