Coworking Before Coworking #2: Architecture Against Death

If Andy Warhol’s Factory was a space where art and work became indistinguishable, then the projects of Madeline Gins and Shusaku Arakawa went one step further. They asked whether architecture itself could blur the ultimate boundary between life and death.

In the 1990s, the Japanese conceptual artist Arakawa and the American poet–philosopher Madeline Gins developed what they called Reversible Destiny architecture, an architectural philosophy that aimed to solve what they described as ‘the ultimate human design flaw: death’. Their buildings were not comfortable, not neutral, not even particularly habitable. However, they were certainly alive, and they demanded that those who entered them be alive too.

The Architecture of Difficulty

Most architecture is designed to make life easier: smooth floors, right angles, predictable surfaces. Arakawa and Gins wanted the opposite. Their projects were deliberately awkward, filled with ramps, uneven terrain, tilted walls, and rooms that defied conventional geometry.

Their most famous work, the Reversible Destiny Lofts – In Memory of Helen Keller (Tokyo, 2005), looks like a dream rendered in plastic. Floors undulate like sand dunes; ceilings dip low in unexpected places; walls curve into strange ovals; doors disappear entirely. It is both a building and a provocation — a demand that you stay awake to the world.

As their project manager ST Luk once explained, “Our bodies are conditioned by our surrounding environments. Once you feel comfortable, your body begins to deteriorate. The architecture basically tries to keep you from fully adapting to it”.

To live in one of these spaces is to be continually reminded of your own balance, perception, and fragility. The houses, parks, and installations created by Arakawa and Gins were meant to keep people conscious, literally and existentially, through constant physical engagement.

Artists Before Architects

Both Arakawa and Gins began not in architecture but in art. Arakawa, born in Nagoya, was a central figure in Japan’s postwar avant-garde before moving to New York in 1961. Two years later, he met Madeline Gins, a poet and philosopher whose 1969 book Word Rain explored the materiality of language and perception.

Together, they created a monumental project called The Mechanism of Meaning (1963–1973), an 80-panel series of textual and visual experiments that forced viewers to think about how the body encounters ideas. From there, it was a small but radical leap into architecture; to construct spaces that embodied those same questions.

As curator Irene Sunwoo of Columbia GSAPP observed, “When was the last time you heard about a poet working in architecture with a painter?”.

Reversible Destiny

The phrase “Reversible Destiny” sounds mystical, but what they meant was deeply embodied. Death, they argued, was not inevitable but the result of a gradual surrender to habit, comfort, and environmental passivity. To resist death, then, was to resist adaptation — to keep the body and mind in a state of creative unease.

Their later projects included the Site of Reversible Destiny – Yoro Park (Gifu Prefecture, 1995), a landscape so disorienting that visitors are given helmets at the entrance; the Bioscleave House (East Hampton, 2008), with its rolling orange floors and asymmetric architecture; and even the Biotopological Scale-Juggling Escalator (2013), designed for Rei Kawakubo’s Comme des Garçons store in New York.

Each was an experiment in rethinking how space shapes life. Each invited its inhabitants to “choose everything” as the pair often said, to reject professional categories, artistic hierarchies, and even mortality itself.

Living Architecture

In an age when design is often reduced to lifestyle, Arakawa and Gins offered something more radical: architecture as existential resistance. Their buildings rejected passivity. They turned space into a tool for staying conscious.

The point was never simply to live longer, but to live more intensely; to experience the world through all the body’s capacities: sensory, intellectual, imaginative.

As curator Sunwoo put it, “Reversible destiny is not about eternal life. It is a prompt to understand how to live to your fullest - to understand how your body interacts with the world on every single level”.

Why This Matters to Coworking

At Rebel Workspace, we see this lineage as more than historical curiosity. The philosophy of Reversible Destiny reminds us that architecture can be alive; that space is not neutral but active, shaping how we think, move, and collaborate.

Coworking spaces are not just real estate. They are social machines for generating awareness, creativity, and connection.

Arakawa and Gins challenged the idea that comfort equals happiness. Perhaps in work, as in life, growth requires a little disorientation, a little friction; a refusal to adapt completely.

That, in many ways, is what Rebel Workspace stands for: living architecture for living ideas.

References

Ciampaglia, D.A. (2018). “These Architects Sought to Solve the Ultimate Human Design Flaw — Death.” Metropolis Magazine, 30 May.

Reversible Destiny Foundation (2024). Projects & Philosophy. New York.

Gins, M., & Arakawa, S. (1997). Architectural Body. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

COWORKING BEFORE COWORKING #1: Warhol’s Factory

Coworking Before Coworking #1: Andy Warhol’s Factory

Before the term “coworking” existed, there were already places where creativity, community, and commerce collided. They were not called incubators or creative hubs, but they performed the same function. These were spaces where artists, thinkers, and entrepreneurs gathered to experiment and work outside conventional systems.

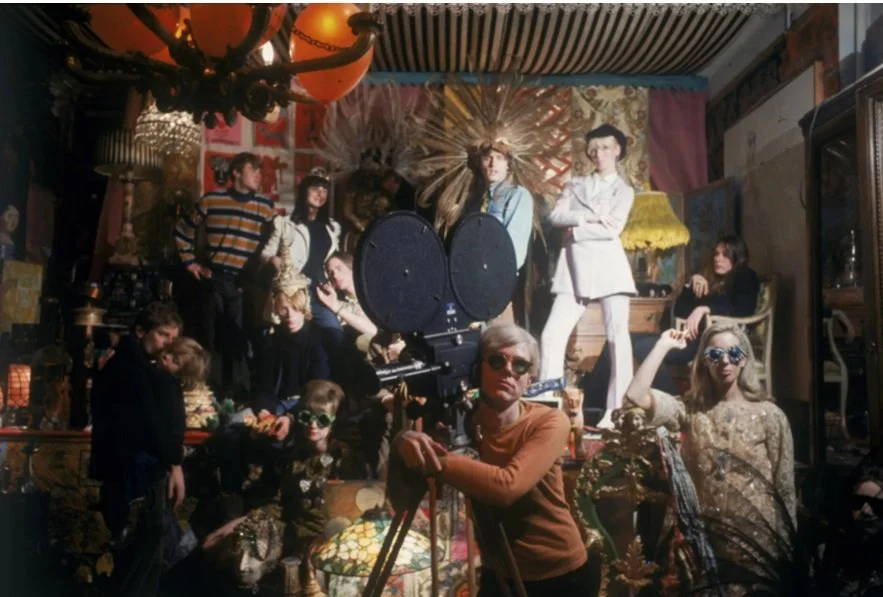

One of the most famous of these was Andy Warhol’s Factory, perhaps the most iconic shared creative space of the twentieth century.

The Silver Factory, 231 East 47th Street, Manhattan

Warhol opened his first Factory in 1964 at 231 East 47th Street in Midtown Manhattan. The space was decorated entirely in silver. The walls, ceiling, and furniture were wrapped in foil and coated in metallic paint by artist Billy Name. This aesthetic decision was both minimalist and excessive. It reflected the industrial age’s fascination with machinery and surface while creating a dreamlike environment that blurred the boundaries between art, commerce, and performance (Bockris, 2003).

The Factory was simultaneously a studio, film set, gallery, and party venue. Warhol shot many of his underground films there, including Vinyl (1965) and Chelsea Girls (1966). The Velvet Underground rehearsed within the same walls, merging avant-garde art with experimental music. Screenprints of Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor were made on site, often by untrained visitors or friends. Mistakes became part of the aesthetic.

Gallerists were sold unframed canvases often made by attendees of the various happenings at The Factory, which were nevertheless sold as unique Warhols. This approach to artistic production was detached yet democratic, parodying the production lines of industrial capitalism and redefining the idea of artistic authorship. The Factory was a site of production but also a social experiment in distributed creativity.

A Factory that Manufactured Culture

Warhol’s choice of the word Factory was deliberate. In an era defined by Fordist mass production, he turned the language of industry inward. His Factory did not produce cars or machinery. It produced images, myths, and cultural moments. In place of hierarchy, it cultivated participation. It embodied what Walter Benjamin described as the paradox of mechanical reproduction, where art and labour, originality and repetition, become inseparable (Benjamin, 1936).

What emerged was a new model of creative work: collaborative, performative, and open to influence. Warhol’s practice blurred the line between fine art and popular culture, while the Factory blurred the distinction between artist and assistant, professional and amateur, work and play.

The First Coworking Space?

If coworking today represents a shift from private offices to shared environments that value flexibility, collaboration, and community, then Warhol’s Factory anticipated this model by more than half a century. It was a precursor to the creative economy, where value is generated through networks rather than hierarchies, and where work and identity merge.

The Factory’s participants were artists, musicians, writers, photographers, and drifters. these all coexisted in an open system of creative exchange. Like a contemporary coworking space, it functioned as both a site of production and a stage for self-presentation. The Factory demonstrated that creative energy thrives not in isolation but through proximity, friction, and experimentation.

The Rebel Connection

At Rebel Workspace, we take inspiration from the Factory as an organisational and ideological model, as well as just a beacon of smouldering cool which we want to emulate. The Factory teaches us that true coworking is not about ergonomic chairs or filtered water. It is about creating environments where risk, experimentation, and collaboration are encouraged. The Factory reminds us that innovation rarely comes from corporate settings. It happens in the margins, in spaces where people are free to make, to fail, and to invent together.

Warhol’s Factory was more than a studio. It was an early prototype for the coworking ethos, a collective reimagining of what work could be.

References

Benjamin, W. (1936) The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. New York: Schocken Books.

Bockris, V. (2003) Warhol: The Biography. London: Da Capo Press.

Colacello, B. (1990) Holy Terror: Andy Warhol Close Up. New York: HarperCollins.

Watson, S. (2003) Factory Made: Warhol and the Sixties. New York: Pantheon Books.

welcome to the rebel zine

It all begins with an idea.

editor’s introduction

This is not a blog. It is a feed from the underground.

The Rebel Zine takes its cue from the radical underground press that exploded across Britain in the late 1960s and 70s. Titles like International Times, Oz, Frendz, Black Dwarf, Sniffin’ Glue, Anarchy, Gay Left, Heatwave, and Spare Rib broke away from the mainstream and invented new cultural languages. They were messy, loud, experimental, and unapologetically political.

Spare Rib, launched in 1972, became one of the most important. Its title was an ironic reference to the biblical rib of Adam from which Eve was supposedly formed, a reminder of how women were treated as secondary or “spare.” The magazine turned that insult into power, declaring that what society dismissed or marginalised could be pulled into the centre of the conversation.

The Rebel Zine carries that same energy forward. It is our space for experiments, fragments, and provocations. It lives somewhere between a sketchbook and a magazine, a place where unfinished ideas collide with finished visions. Here you will find dispatches from our community, reflections on culture and work, and the messy beauty of making something new. Heritage buildings turned into creative playgrounds. Late-night conversations that spill into manifestos. Music, art, fashion, design, and the kind of raw energy that refuses to sit quietly.

Some of what appears here will be sharp and polished. Some will be rough, unfiltered, and direct. All of it will be unapologetically rebellious. The Rebel zine will be composed of challenges, provocations, ideas, experiments, and dispatches from inside our community. Late-night collisions between founders and artists. Secret gigs in boardrooms. The messy, beautiful work of building something new.

Some of what we publish here will be raw. Some will be refined. All of it will be unapologetically Rebel.

Stay tuned. The revolution does not knock. It breaks through the door.